Apocalypticism and the Islamic State

November 17, 2015

The Islamic State (IS) was never a part of the legitimate resistance against Syrian President Bashar al Assad. There are possibly hundreds of opposition groups inside Syria. Several of these groups consider themselves to be the leader of the rebellion. These groups are not part of a larger monolithic whole; rather, they are divergent ethnic and religious groups that are often antagonistic and even violent towards one another.

The Islamic State has used the chaos created by the Syrian rebellion to try and fulfill an obscure Islamic prophecy. Back during the zenith of Osama bin Laden’s war with the West, some Islamists started focusing on any Islamic teachings, no matter how obscure, that promoted a jihadist vision that would be global in scope. Their goal was to legitimize their politicized version of Islam and to cement the legitimacy of jihad in the minds of Muslim moderates. This search led to scholarship regarding something called Yawm ad-Din, the Day of Judgement.

that would be global in scope. Their goal was to legitimize their politicized version of Islam and to cement the legitimacy of jihad in the minds of Muslim moderates. This search led to scholarship regarding something called Yawm ad-Din, the Day of Judgement.

Eschatology is a part of theology concerned with the final events in history. Such a concept is often referred to as “end times” and it is definitely not limited to Islam. Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Baha’i, and new religious movements such as New Age religions also have eschatological theology and followers who believe in imminent apocalypticism

The Day of Judgement was first introduced to jihadi groups by the world’s foremost jihadist scholar, a Palestinian man named Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi. Maqdisi’s prominence and knowledge has attracted jihadi acolytes over the years including Abu Mus’ab al Zarqawi. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) called upon Maqdisi to find out if their jihad in Yemen would lead to an Islamic Caliphate. Maqdisi affirmed an exceptional destiny for the jihadists in Yemen, but added a caveat that the group in Yemen would have to go on to Syria to fulfill their destiny. Maqdisi explained that AQAP would help bring about Allah’s judgment by helping to usher in the end of the world. Maqdisi explained that jihadists in the AQAP would help mobilize popular support against the West and its apostate allies by launching attacks all over the globe. But first, the fighters in Yemen had to get to Syria.

Yemeni fighters poured into Syria, but the original al Qaeda and its affiliate the Islamic State of Iraq would play a part in popularizing Syria’s role in bringing about the Day of Judgement.

Abu Bakr al Baghdadi assumed control of the Islamic State of Iraq in 2010. Baghdadi’s closest aide, Hajji Bakr, who has been described as the “prince of the shadows,” helped his leader consolidate power. He proclaimed Baghdadi as a legitimate caliph that was helping to usher in the apocalypse. Baghdadi’s followers believe there will only be four more caliphs after Baghdadi before the end of the world.

During this period, Bakr saw jihad in pragmatic terms. He wanted to attack government troops and police as a blueprint to open up power vacuums to deplete security and resistance to an Islamic State takeover. He also wanted to introduce a powerful religious motivation for uniting jihadists behind a single program—his program. The Day of Judgement prophecy became an influential tool for motivating jihadists to take over Iraq and Syria under Baghdadi’s control.

When Syrians began peaceably protesting against their government in 2011, Assad’s administration released an unknown number of jihadists from prison with a calculation that these men would foster violence among the protesters and give the regime an excuse to violently suppress them. Taking advantage of the volatility, al Qaeda’s Ayman al Zawahiri encouraged Baghdadi to send members of his Islamic State of Iraq into Syria. He did, and this group morphed and eventually came to calling itself Jabhat al Nusra or Nusra Front.

Nusra expanded in Northern Syria, and it eventually splintered with the Islamic State of Iraq.

In 2013, Baghdadi announced that he was in control of Nusra and that he was merging it with the Islamic State of Iraq into one group, “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (ISIL or ISIS). Some leaders within Nusra rejected this merger and reaffirmed an allegiance to al Qaeda. Others, particularly foreign fighters from Yemen, joined with Baghdadi.

The end times prophecy worked as a solidifying agent and as propaganda to bring jihadists groups under Baghdadi’s control.

The Qur’an does not go into much specificity about the Day of Judgement. Instead, Islamists have had to depend on hadith for descriptions and guidance. Various hadith explain that chaos and corruption will rule in Muslim lands, and Jesus (whom Muslims see as a Muslim and a Prophet) will return near the day of judgement to restore justice and to defeat the Antichrist called the Mahdi. After he defeats the Mahdi, Muslims believe that Jesus will assume leadership of the world and will live for another 40 years before dying of natural causes. The rule of Jesus will be the precursor to Muhammad returning for the final day of judgement.

The prophecy that the Islamic State has used is a version of this narration. It describes that the armies of “Rome” will gather on what are currently grasslands in Northern Syria. These armies will face off against the armies of Islam (Islamic State) and then be vanquished. IS will then be free to takeover Istanbul before a final showdown in Jerusalem. It is there in Jerusalem that Jesus will return to slaughter the Antichrist and his followers the Christians and Jews.

Most Islamic sects consider hadith to be essential supplements to, and clarifications of, the Qur’an. Sunni and Shi’a hadith collections differ drastically. Sunni hadith texts number around 10 thousand. Shi’ites refute six major Sunni collections, but Shi’a sects cannot agree with one another on which of their texts are actually authentic. Consequently, hadith texts within Shi’a traditions are more contested, and therefore an exact number for Shi’a hadith is difficult to claim.

Sectarianism and Tribalism Weakens Iraqi Resolve

June 30, 2015

When the Iraqi city of Ramadi fell last month to the terrorist group calling itself the Islamic State, it was a big defeat. Ramadi is a provincial capital just 60 miles west of Baghdad, and its capture is not just seen as a strategic loss, but also a symbolic one.

Iraqi forces, on numerous occasions, have fled from the Islamic State. Iraq’s military abruptly absconded from Mosul last year. In Tikrit, Iraq’s security forces were failing to turn the tide of battle, so Shi’ite militias had to be brought in to liberate the city. And in Ramadi, Iraqi troops turned tail and ran.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi sought to deflect blame over the weekend with a televised appearance. He said troops had never been authorized to withdraw from Ramadi, and insisted his orders, “were the opposite.” Mr. al Abadi asserted that if troops had followed orders and stayed, Ramadi would still be under government control.

Iraq’s Prime Minister came to power vowing to mend sectarian fractures that were exasperated under his predecessor, Nouri al Maliki. Sectarianism has been cited as one of the main contributing factors for why the Islamic State has so easily conquered large cities in Sunni areas of the country. To put it simply, Iraq’s Shi’ite government has been unable to galvanize alienated Sunni soldiers to fight on its behalf.

The changes that have occurred in Iraq’s political process since Saddam Hussein’s fall from power have upset the established and seemingly stable relationships that existed before the Iraq War. Shi’ite forces taking over the central government hint at far-reaching shifts in regional distributions of power, an unleashing of renewed religio-political forces, and a realignment of tribal relations.

The city of Ramadi is the provincial capital of Anbar Province which is, geographically, the largest governorate in Iraq. Encompassing much of Iraq’s western territory, Anbar Province shares a border with Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. Anbar’s provincial council has requested assistance from Shi’a militias to free Ramadi from Islamic State control. Since Anbar Province has a mostly Sunni population, there are risks to Shi’ite militias engaging the Islamic State there.

Many fear that Shi’ite militias would further fuel the sectarian conflict that underlies everything that’s going on in Iraq. There are concerns that there will be reprisals from Shi’ite militias against Sunnis in the area; however, the fact that Anbar’s Sunni leadership has called for Shi’a assistance is a sign of how desperate the situation has become. Anbar’s provincial council has lost faith in Iraq’s military.

Sectarianism isn’t the only thing that hinders Iraq’s armed forces. US troops training and advising the Iraqi military on combating the Islamic State have found that Iraq’s military leadership is plagued by tribalism and cronyism. The US Army’s No. 2 general, Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Daniel Allyn, has found that tribal factions have degraded the training and readiness of Iraq’s security forces. This is a huge problem, because Sunnis who do not feel a particular loyalty or allegiance to the Islamic State have lost confidence that the government is going to protect them. This makes it that much harder for these Sunnis to trust the government’s promises, and to agree to work with government forces to organize themselves.

Capitalizing on Iraq’s sectarianism, the Islamic State has developed a narrative that it defends Sunnis against Baghdad.

Some in Iraq have sought to combat the Islamic State by using the theme of reconciliation as a competing narrative. This involves careful cooperation between Shi’ite militias and Baghdad-allied Sunni tribes, and there is evidence it is working.

Representatives from a Shi’ite militia in Najaf, Iraq recently held a meeting on reconciliation with Sunni tribal leaders in the area. After the meeting, all of the Sunni tribes agreed to hand over the Islamic State collaborators from within their ranks.

Iraqi forces will need a wide array of tools to defeat the Islamic State. Along with Ramadi, the Iraqi government has lost control of about 90% of Anbar Province and most of the “Sunni Triangle.” The security forces that have proven effective, the Shi’ite militias and Kurdish Peshmerga, will likely be a source of future conflict if the fight with the Islamic State is ever brought to a successful close.

Since the Islamic State has taken over Ramadi, it has established two Islamic courts and a police force to keep order and maximize its control over the population. It has seized pension payments from former Iraqi civil servants and retired military. Most concerning, however, are the stories of Islamic State soldiers going door to door with a list of names, and that they are killing people who they believe to be supporters of the Iraqi government. The Islamic State is trying to observe Ramadi’s population twenty-four hours a day to see who might be secretly sending information to Baghdad and to the Americans.

Saudi Coalition Weakens Iranian Influence

March 30, 2015

Foreign ministers of the Arab League last week announced their agreement to form a Joint Arab Strike Force for rapid intervention in troubled hot spots.

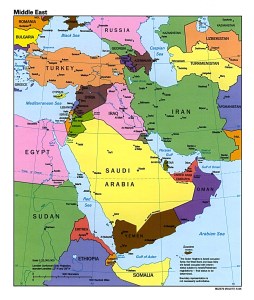

This announcement constituted a formidable alliance to fend off Iranian influence in the region, and firmly established the kingdom of Saudi Arabia as the leader of the Arab world. The regional coalition has been in the works for months, and is made up of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, and Sudan.

Under the auspices of this coalition, Saudi Arabia has launched operation Decisive Storm wherein precision airstrikes have been unleashed on its southern neighbor, Yemen.

Saudi Arabia is bombing Houthi rebels who have been taking over Yemen. This is the latest installment in a long simmering proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran for regional power.

The Houthis, who are financed by Iran, are strongly anti-American as well as opponents of Sunni regimes like Saudi Arabia. The Houthis are dominated by a Shi’a Muslim sect, the Zaydis.

Yemen, at the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, has long been a tinderbox. The American-backed government in Yemen abruptly collapsed in January. The resignation of the president, prime minister, and cabinet took many by surprise and heightened the risks that Yemen, the Arab world’s poorest country, would become even more of a breeding ground for terrorism. It was in this vacuum that Iran hoped to expand its influence.

The launch of operation Decisive Storm has been in play since the accession of Salman Bin Abdul Aziz to Saudi Arabia’s throne. King Salman was crowned in January and has quickly moved to address Saudi public opinion which has been getting increasingly worried about Iranian power surrounding the kingdom and perceived Saudi impotence in opposing the Iranian threat.

The Iranian response has reportedly been one of shock. The Iranian defense council is said to have met at 3 a.m. Tehran time on Thursday morning after receiving news of the airstrikes. The Iranian intelligence services did not anticipate such airstrikes, because Iran miscalculated the regional response to its expansion.

To complicate matters for Iran, it and Yemen do not share a border. The Iranian government is worried how it will recover the missile systems, intelligence and surveillance systems it has placed there.

Iran has supplied the Houthis with weapons systems that can hit almost anywhere in Saudi Arabia including government buildings, landmarks, and infrastructure.

The airstrikes are designed to take out as much Iranian sponsored Houthi military equipment as possible.

Operation Decisive Storm has seven stages; first is the destruction of the Houthis air-power, then their air defense systems. This will be followed by flushing out any pockets of air resistance. The fourth stage is the establishment of air superiority to be followed by the establishment of complete control over the theater of operations. The sixth stage is the apprehension of key figureheads, and finally redeployment of Yemeni forces into the theater.

The land forces that will be deployed will be formed out of Yemeni special forces, tribes and factions loyal to former Yemeni President Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi while Saudi Arabia’s coalition forces will be ready to assist or intervene as well as providing air support for ground operations.

Saudi and Egyptian warships have been deployed to the strategic Bab al-Mandab strait, a key trade and oil route separating the Arabian Peninsula from east Africa.

It will be important to redeploy the Yemeni special forces because neither the Saudis nor the Egyptians are likely to be able to match the Houthi and their allies in combat in mountainous terrains in which familiarity with the grounds will prove a major advantage.

The Saudi coalition is arguably one the most significant developments within the Middle East in decades, because it is a complete reversal of Saudi Arabia’s former policy of quiet disengagement with its neighbors. It also reflects the emergence of two young Saudi leaders: the Deputy Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef and the Defense Minister and Royal Court chief Prince Muhammad bin Salman. This kind of proactive policy is not in traditional Saudi style and the credibility of these two men will be heavily impacted by the success or failure of this operation.

However, it is Saudi Arabia’s new King Salman who most threatens Iran’s dreams of expanding its power.

There is a danger that the longer this campaign continues, the more damage will be done to stability inside Yemen. Instability is a breeding ground for terrorist groups.

Another worry is that the Arab nations’ intervention in Yemen may cause them to lose interest in a different war – the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Most of the members of Saudi Arabia’s coalition are also members of the U.S.-led coalition in Syria that’s been waging an air campaign against ISIL.

As they begin to focus on the Yemen problem, the coalition’s resources will be used less in Syria.

UAE Cabinet of Ministers to vote on Counterterrorism Law

July 29, 2014

The United Arab Emirates Federal National Council approved last week a revised draft of its 10-year-old counterterrorism law to respond to evolving threats.

If the new law is approved by the UAE Cabinet of Ministers and signed by President Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al Nahyan, a person need only threaten, incite or plan any terrorist act to be prosecuted as a terrorist. Furthermore, crimes committed “with terrorist intent” would carry much greater penalties than those without.

The law would also authorize the UAE Cabinet to set up lists of designated terrorist organizations and persons. The Cabinet can also establish prison centers to give convicted terrorists intensive religious and welfare counseling to dissuade them from extremist views.

Virtually all native Emeratis are adherents of Islam. Approximately 78% are Sunni and 22% are Shi’ite. The ruling families are Sunni and support the Mālikī school of jurisprudence. The Mālikī school differs from the other Sunni schools of law most notably in the sources it uses for derivation of rulings. All schools use the Qur’an as primary source, followed by the prophetic tradition of the prophet Muhammad, transmitted as hadiths. In the Mālikī school, said tradition includes not only what was recorded in hadiths, but also the legal rulings of the so-called four rightly guided caliphs.

It is important to note that if the list of terrorist groups to be drawn up under this law is seen by the UAE’s neighbors or other countries as politically motivated, that could undermine the law’s perceived legitimacy.

The 2004 law primarily addressed terror financing. All UAE banks were placed under the authority of the Central Bank through its Banking Supervision and Examination Department, which monitors banks and other financial institutions. The law allows the Central Bank to freeze funds anywhere in the UAE, and to monitor accounts that may be used to facilitate terrorism.

In recent months, media reports have depicted a number of Emirati citizens who were killed in the fighting in Syria with Islamic factions.

In May, nine people were tried on charges of supporting the Jabhat al Nusra Front in Syria. The state news agency WAM reported that UAE state security prosecutors have accused seven of the defendants of joining the terrorist al Qaeda organisation and forming a cell in the UAE to promote its ideas,. It said the men had tried to recruit members to join al Nusra that is fighting the Syrian government and had raised money that they sent to the organization.

The two other defendants were accused of running a website promoting al Qaeda’s ideology and aimed at “recruiting fighters to execute terror acts outside the country” according to WAM.

No terrorist attacks have occurred in the UAE to date.

The Splintering of Iraq

June 18, 2014

Shi’ite militias have mobilized in Iraq to battle the Sunni insurgent group the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Shi’ite gunmen have marched through Baghdad and taken control of a town northeast of the capital to stage a battleground to stop the advance of the fundamentalist group.

ISIS has taken a full province, Nineveh province, including Mosul (the second-largest city in Iraq) and parts of three others.

The Iraqi army is falling apart, but it’s being bolstered by Shi’a militias responding to a call to arms by the most influential Iraqi Shi’a cleric in the world (Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani) who said that people should take up arms to defend against this group. He said, “He who sacrifices for the cause of defending his country and his family and his honor will be a martyr.”

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki said the government would arm and equip citizens who volunteer to fight. Al Maliki has declared a state of emergency and claims he’s been given all powers to fight this threat. According to his critics, however, al Maliki is the reason that ISIS has been so successful in winning Sunni allies in Iraq, because al Maliki has ruled in a very sectarian and corrupt way. He’s a politically embattled figure.

Al Maliki has pushed out a lot of influential Sunni leaders, and that’s why ISIS is getting the support that it has right now, because a lot of the Sunni community in Iraq feels marginalized and afraid of the al Maliki government.

As I said in a post yesterday, ISIS has taken advantage of a wave of Sunni anger in Iraq, and ISIS has gained allies among Sunni tribal leaders, ex-military officers under Saddam Hussein, and other Islamist groups in Iraq. The authority ISIS wields in Iraq is not yet part of a larger monolithic whole; rather, ISIS relies on divergent Sunni tribes, organizations, and groups that can be antagonistic and even violent towards one another.

Most of the ISIS fighters in Iraq have poured over the border from Syria, and many come from al Qaeda and affiliated groups such as Jabhat al Nusra. These groups promote a jihadist vision that is fanatically anti-Shi’a. One of al Qaeda’s main reasons for getting involved in the war in Syria has been its grievance that the Syrian regime is run by Alawites, people who belong to a branch of Shi’a Islam.

ISIS must retain popular Sunni support in Iraq to ensure that other Sunni groups are willing to work with them if ISIS hopes to maintain its hold on Iraqi territory. However, it is unclear if that support will last.

Some Sunni clerics in Mosul and Tikrit, which are under the control of ISIS, have been executed by ISIS insurgents for not showing allegiance to the organization. ISIS militants are said to have executed around 12 leading clerics in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul. According to Al Alam News, an imam in Mosul’s Central Mosque was executed for refusing to join ISIS insurgents in their cause. Executions have also been reported in Tikrit.

Meanwhile, refugees are flowing into the Kurdish north from Mosul and surrounding areas. The Kurds are taking disputed territory abandoned by the Iraqi Army, including a border point with Syria.

Kurdistan is a semiautonomous region. It has its own system of laws and governance, and it has long wanted its own independent country. The Kurds are also fighting ISIS, but they are taking advantage of the collapse of the Iraqi military at the same time. The Kurds are taking the territories they feel should be part of their future state, including Kirkuk and this border point.

Last week, ISIS used the social media device Twitter to announce that it had executed 1,700 Shi’a soldiers, and it has tweeted graphic pictures of the executed to support its claims.

Why Iraq is Failing

June 17, 2014

On Sunday, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) claimed to have captured and slaughtered hundreds of Iraqi Shi’ite Muslim soldiers.

Mosul and Tikrit were taken in a matter of days by Islamic insurgents, and those insurgents are now moving toward Baghdad.

ISIS looks more like a well-organized army than your typical ragtag insurgent group. ISIS seized at least $500 million in Mosul alone by raiding banks. They’ve also done very well from the oil fields of eastern Syria. The conservative intelligence estimate is that this organization now has cash and resources of around about $1.2 billion.

ISIS is robust, it is organized, and it is very, very disciplined.

ISIS is attempting to press home its agenda, which is to enforce an Islamic caliphate and to oust the Shi’a power base in Iraq. It’s attempting to do this with a two-pronged approach—ruthless military force on one hand and quiet coercion on the other—as it attempts to establish itself among the Sunni communities.

Shi’ite Iran is a key ally of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his Shi’a dominated government. Iran is deeply worried that ISIS could destabilize and weaken Shi’ite political influence.

That ISIS could so swiftly move on Mosul and Tikrit reveals the depths of Iraq’s sectarian divide. Mosul is a predominantly Sunni city long alienated by the mostly Shi’ite government in Baghdad. ISIS rode that wave of Sunni anger, finding allies among Sunni tribal leaders, ex-military officers under Saddam Hussein, and other Islamist groups in Iraq. The national army didn’t put up a fight.

The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria spells out its motivations in its name and now controls a state-sized territory that spans from northern Syria to western Iraq. Two conflicts have been merged—the Syrian Civil War and a larger one looming in Iraq—erasing an international border.

Conflict in Iraq is currently being fought between non-state actors: between a Sunni insurgent group who cares very little about Western drawn and artificial nation-state borders, and Shi’a irregulars who were extremely active in the Iraqi sectarian war in 2006 and are now quickly reorganizing.

That Iraq has remained intact as a nation this long is nothing less than a miracle.

Before World War I, the Ottoman Empire controlled the Arab world via a decentralized system of provinces (vilayets) along tribal, religious, and sectarian lines. These vilayets were subdivided into sub-provinces (sanjak) under a mütesarrif, then further divided into jurisdictions (kaza) under a kaimakam, and finally into communes. Constant regional conflicts made the Arab world a continuously volatile and unpredictable place, and the iron fist of Ottoman rule kept only an appearance of order. Any attempt of a more centralized system of government would have made the Ottoman Empire unmanageable.

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire crumbled. The majority of its non-Anatolian territory was divided up among the Allied powers as protectorates. The Western idea of nation building sought to give a modern agglutination to the Arab world by constructing new kingdoms of their own design. The aim was simple: create new royal families who would yield to Western strategic interests.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Iraq was divided into three vilayets: Baghdad, Mosul, and Basra. After World War I, Britain imposed a Hāshimite monarchy over Iraq. Territorial boundaries were drawn without taking into account the tribal, religious, and sectarian politics that plagued the region. The establishment of Sunni domination in Iraq brutally suppressed the majority Shi’a population.

Iraq has been a turbulent place ever since. In 1936, the first military coup took place in the Kingdom of Iraq. Multiple coups followed, and Iraq has been characterized by political instability ever since.

The Ba’ath Party took power in 1963 after its leadership assassinated their political rivals. The Ba’ath government stagnated Kurdish insurrection, suppressed Shi’a communities, and disputed territory with Iran and Kuwait. Saddam Hussein, the final and most notorious leader of the Ba’ath Party, maintained power and suppressed Shi’ite and Kurdish rebellions with massive and indiscriminate violence.

The Ba’ath Party was infamous for having a class orientation that marginalized millions in the poorest sections of Iraqi society. Southern Iraq and some areas of Baghdad, populated mostly by Shi’a migrants from southern rural areas, have historically been home to the poorest people.

Iraq’s modern history has seen the most serious sectarian and ethnic tensions following the 2003 US-led occupation. There is plenty of collected anecdotal evidence that suggests that the elites of the Ba’ath Party were targeted by the poor and oppressed before the Ba’athist regime fell to US-led coalition forces. The US-led occupation then exacerbated conditions on the ground by promoting Iraqi organizations that were founded on ethnicity, religion, or sect rather than politics. These policies emphasized differences and divided coexisting communities.

Because the modern nation-state of Iraq is made up of territorial boundaries originally designed and imposed by the British, warring groups over tribal, religious, and sectarian lines have been condensed together. So far, authoritarian regimes have been the only systems of government that have had success at keeping the integrity of these boundaries intact.

Under the Ottoman Empire, territorial borders were changed constantly reflecting the emergence of new conflicts, the changing nature of older conflicts, and the rise of powerful threats. Subdivisional borders were porous and tribes traveled through them constantly giving extreme variability to population figures.

The idea of dividing Iraq into smaller states was floated by the US-led coalition that invaded and occupied the country. If the current success of ISIS in capturing a state-sized territory from northern Syria to western Iraq has shown us anything, it is that the Western idea of nation building is failing in that part of the Middle East. The Ottoman Empire has been gone for less than 100 years, and that is a very short time to expect an entire region of varying peoples and communities to completely change their worldview, overcome their differences, and get along.

Instead, maybe the Western cognitive orientation of the Middle East, based on Western interests and state security, is what needs to be changed. At the very least, it needs to be reexamined. If conflict in Iraq breaks that nation-state back into smaller pieces, is that really such a bad thing? Is it really that important to keep artificial boundaries that were created by Western powers with little to no regard to what the citizens of that country wanted?

Whatever the outcome, the people of Iraq should decide their own fate.

The ISIS offensive has thus far been successful in Iraq, but it will most likely be stalled north of the Shi’a-dominated capital of Baghdad. This will potentially split Iraq along an ethno-religious-sectarian divide. This could lead to a prolonged and bloody standoff that could see the current borders of Iraq crumble.

Syria Has Used Chemical Weapons

April 26, 2013

United State’s President Barack Obama’s administration has assessed that Syria has likely used chemical weapons twice in its civil war. This has intensified calls where I work on Capitol Hill for a more aggressive U.S. intervention in Syria. However, American lawmakers are far from agreeing on what a greater American role would look like.

The U.S. intelligence community has determined that Syria has crossed the red line set out by Mr. Obama, who has said the use or transfer of chemical weapons would constitute a “game changer” to his policy of providing only humanitarian and nonlethal assistance to the Syrian opposition.

U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel announced the news yesterday during a trip through the Middle East. “It violates every convention of warfare,” Hagel told reporters in Abu Dhabi.

Several U.S. Senators have since renewed their calls for stronger U.S. intervention in Syria without United Nations involvement.

New Jersey Democrat Robert Menendez, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, says that he supports working with regional partners, establishing a no-fly zone with international support, and potentially arming vetted rebels in some sort of controlled process.

“It is clear that we must act to assure the fall of Assad, the defeat of extremist groups, and the rise of democracy,” Menendez said in a written statement.

However, calls for intervention in the Syrian civil war are being met in the U.S. and elsewhere with trepidation.

The Syrian military’s defense mechanisms are sophisticated and located within major population centers. Removing those devices could cause mass civilian casualties. This will make instituting and maintaining a no-fly zone very difficult. Furthermore, potential ethnic divisions within the country are severe.

There is also a lot of concern within the Western intelligence communities about who some of these various groups are aligned with. Some groups have ties with al-Qaeda and other groups have ties to other jihadi organizations. Another particular concern is the role that Hezbollah may be playing in the war.

Hezbollah is a Shi’a militant group. It has a paramilitary wing that is one of the stronger militant movements within the Middle East. Hezbollah has been a recipient of financial assistance from Syria for years, and what actions it is taking during the civil war remains unclear. Hezbollah would be one actor that could stand in opposition to al-Qaeda (a Sunni organization).

Indeed, there are reports coming out of Syria that sectarian conflict, between Shi’a and Sunni groups as well as between tribes within those denominations, is erupting in the wake of conflict between rebel forces and the military.

The Syrian civil war is a very complicated contest. The breakdown along ethnic lines will be every bit as problematic as it was in Iraq – only Syria has chemical weapons.

There are many ways to analyze the ongoing conflict in Syria. It can be seen as a revolution against an authoritarian regime, or as a proxy war between Sunnis and Shi’a, or as means for al-Qaeda and similar organizations to find new relevance. All of these approaches are helpful in understanding the nuances of varying actors and their motivations in the war.

Further debate on a U.S. response to Syria is expected later today after lawmakers receive a classified briefing on the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons.

The White House said that the administration will wait to announce its next moves until a United Nations investigation into the two suspected cases of chemical weapons produces “credible corroboration” of the U.S. intelligence community’s assessment.

Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee, the ranking republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said, “If it is verified, then obviously it is a crossing of the red line and would greatly change our posture there.”

The Power of Religion in the Middle East

April 24, 2013

Amid the unrelenting political turmoil of the Middle East, in which loyalties and alliances can shift with the winds (commonly referred to as the Arab Street), Islam is often the only common denominator. For the average citizen, life can be very very difficult; and, as a result, Islam is very attractive, because it offers some sort of hope for eternal peace. Islam also offers a unifying power for leaders, and it can be used as a justification for political or military campaigns.

Islam’s following has grown from a handful of converts to one of the fastest growing religions in the world. Many politicians and strongmen in the Middle East have found that the best and most expedient way into the hearts and minds of their people is through their souls. Emphasizing religious ties can win leaders support and help them cement their power. In this way, religion can be utilized as a means of influencing the behavior of people.

Through religion, military campaigns can be transformed from territorial plunders to a holy war fought in the name of “faith.” The idea that God will be on the side of good can also be used as a supremely powerful stabilizing force during battle.

However, just as Islam can unite populations, it can also divide them. The cultural divide that already existed in the Middle East turned religious and political when Islam split into two halves.

The conflict between Sunni and Shi’a is the most consequential in the Middle East, because it is so profound.

Shi’a Islam, whose followers constitute a mere 15 percent of the world’s 1.4 billion Muslims, was relegated to second-class status in the Arab world long ago. But in 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini seized power in Iran, he sought to export the ideology of his country’s Islamic revolution to Muslims everywhere, even to Sunni Muslims. This unlikely goal sought to counter centuries of blood-spattered encounters, prompted by deeply felt doctrinal differences. More importantly, this goal was designed to increase Iran’s influence outside of its borders.

Westerners are insensitive to the doctrinal differences between Sunni and Shi’a, viewing them as minor details rather than matters of cosmological importance.

The Sunni-Shi’a split dates back to the seventh-century dispute over who was meant to be the Prophet Muhammad’s rightful successor. Today’s Shi’a are descended from those who believed that Muhammad had chosen his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, as his heir. This was a minority view in the days following the prophet’s death, and one of his lieutenants, Abu-Bakr, was made caliph and successor to Muhammad instead. The schism became permanent after the Battle of Karbala in 680, when Ali’s son Hussein was killed by the caliph’s soldiers.

Institutionalizing this divide left the Shi’a at a grave disadvantage, because the Shi’a did not have the same resources as the Sunnis.

Religion can provide individuals and organizations with agency. It is regularly argued that God’s justice is something that comes down to earth, if one knows how to read it. Those who purport to have this knowledge often gain incredible influence as they can become a center of authority.

With Islam being the dominant cultural force in the Middle East, it is a tool that is often used by revolutionaries who seek to challenge the status quo.

Osama Bin Laden, the architect behind the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, was probably born in 1957, and he was number 17 of 57 children to a father who made a fortune in the Saudi Arabia construction industry. A young bin Laden got his penchant for radical Islamist ideology at his university, King Abdul-Aziz University, in Jeddah.

Bin Laden was influenced by the Sunni reformist movements of Deobandi and Salafi. The followers he gathered were bolstered by a genuine belief that he was reformulating the global order. In 1989, these followers became known as al Qaeda (translated as “The Base”) a multinational and stateless army who believe that the killing of civilians is religiously sanctioned, because of their goal to remake the world in their image.

Bin Laden’s religious rhetoric was designed to persuade Muslim contemporaries that he was a figure who ought to be thought of in biblical terms. He championed a complete break from all foreign influences inside Muslim countries as well as the creation of a new world-wide Islamic caliphate. To achieve these goals, bin Laden funneled money, arms and fighters from around the Arab world into regions where conflict and an increasing lawlessness enabled his growing organization to expand its control over territory.

With each terrorist act, bin Laden became more influential. This is a man who already had money, but craved the ability to coerce whole populations into subjugation.

With bin Laden now dead, the al Qaeda network has thus far failed in its attempts to overthrow the governments of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, and Syria. Perhaps most importantly, it has seen the majority of its monetary assets frozen. Al Qaeda routinely makes public appeals for money. This tells analysts that al Qaeda’s ability to dominate the direction of insurgencies within Asia and the Middle East is waning. But does this mean the network is currently weak? In a word, no. The al Qaeda network is perhaps more dangerous than it has ever been.

Because the appeal of its religiosity remains strong, new fighters are still joining al Qaeda’s ranks. But more significantly, al Qaeda’s financial and logistical problems have forced the network to strengthen its alliances with other groups such as the various Taliban franchises in Afghanistan, the Pakistani Taliban, Balochi and Punjabi extremists, Saudi dissidents, Iraqi and Syrian insurgents, and unaffiliated groups who profit from drug smuggling. This dependence on alliances has caused the network to become as close operationally with outside groups as it has ever been. With these new ties, al Qaeda has also been able to bond ideologically and religiously with other groups like never before. This adds a whole new dimension to the insurgencies in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Syria.

Al Qaeda has used the unifying force of religion to its advantage.

Groups unaffiliated with bin Laden, but touting the al Qaeda name, spring up daily. Like the name Taliban before it, al Qaeda is in danger of becoming a generic term for insurgents groups, and this could make al Qaeda more dangerous than it is now. As it currently stands, al Qaeda is focused on keeping the United States bogged down in conflicts with Muslim fighters. However, if al Qaeda as we know it today looses control of its ideological brand, any new al Qaeda that emerges could use its religious totems to become a more dangerous force. This is because, as Economic theory of Competition explains, competitors encourage efficiency. Competition for the socio-religious clout that comes from being associated with al Qaeda could encourage more ruthless, shocking, and devastating destruction. On the other hand, al Qaeda’s strengthening alliances with other groups could cause the network to loose its strict focus on U.S. interests. If this were to happen, al Qaeda’s still considerable resources could be unleashed on populations in new and unexpected ways – all in the name of religion.

The terror attacks of Sept. 11 caused millions of internet users to search online for their concerns and issues involving religion. According to the Pew Internet and American Life Project (www.pewinternet.org), 23% of users used internet sources to get information about Islam. No doubt, these people wanted to educate themselves on what they were hearing in the media. And since that tragic time in American history, people have continued to use the web as an enormous sacrosanct library. Not only searching for Islam, but a myriad of religions. In doing so, they travel from site to site like virtual pilgrims, they read articles which claim intellectual authority, and they interact with strangers as they swap guidance. In this way, the internet has become a medium for religious communication. However, there is a danger of obtaining inaccurate information on the web. In a world where anyone can post, credentials have become increasingly important.

It is necessary to understand that all religions change over time. They are never static. Religions evolve through reform, revival, and novel developments. Religious understandings change and new beliefs emerge. They both influence and are influenced by the teachings of other cultures. In the end, religion is a cultural product. How it is understood and how it evolves is dependent upon cultural attitudes and cultural arguments. Is Islam a violent religion? Emphatically, no. But, individuals, groups, and networks are attempting to use Islam to justify attacks and murders against those that disagree with them. These men and women have aligned themselves with a violent interpretation of Islam in order to draw media attention, encourage recruitment, and coerce populations.

Amid the political turmoil of the Middle East, Islam is often the only common denominator able to unite populations.

March Is Deadliest Month Yet For Syrian Civil War

April 5, 2013

A Syrian activist group claims that 6,000 people were killed in Syria during the month of March. If true, this would make March the most deadly month yet in the two year-old civil war.

This number comes from the British-based activist group the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. The Observatory gave figures of 1,486 rebels and army defectors and 1,464 Syrian army soldiers killed, along with 2,080 civilians, 298 of them children and 291 women. In addition, the group listed 387 unidentified civilians and 588 unidentified fighters.

An increase in regime artillery could be to blame for the increased death toll: for example, airstrikes from the Syrian air force have had an uptick.

The United States has stepped up its training of the Syrian opposition. The U.S. has also increased providing non-lethal aide to the Syrian rebels including body armor, communications equipment, and food rations.

The Jordanian army has grown its role in training Syrian rebels as well. Jordan would like to set up a humanitarian zone in the southern part of Syria where the two countries share a border. Jordan hopes to employ former Syrian police and army defectors as peacekeepers for the zone.

Plans for a humanitarian zone come as rebels have gained significant amounts of land along Syria’s border crossing with Jordan. The Jordanian government is apprehensive over which factions of the rebellion will ultimately control Syria’s border, however.

An Islamist leaning faction wielding power along the border could complicate Jordan’s plans for the area. A humanitarian zone could be installed in a matter of weeks, and such a place could slow the thousands of people flowing across the border into Jordan. But, this would only occur if Syrians felt the area was safe to stay in. If Islamists ran the zone, there are fears that Syrian refugees will refuse stay there, and Jordan’s government is desperate to relieve the refugee flow into their country.

The Islamist element of the Syrian opposition is complicating more than just plans for a humanitarian zone. There are concerns across the Middle East and here in America that Islamist portions of the opposition could get their hands on some of the heavy arms being given to the rebellion. This gives the Syrian conflict the capability of spilling over Syria’s borders and destabilizing the entire Middle East region along the Sunni/Shi’a divide.

Many of the Islamists in Syria come from al Qaeda and affiliated groups such as Jabhat al Nusra. These groups promote a jihadist vision that is fanatically anti-Shi’a. One of al Qaeda’s main grievances with the Syrian regime is that it is run by Alawites, people who belong to a branch of Shi’a Islam.

The civil war began in mid-March 2011 with mass protests in Deraa as part of the wider ‘Arab Spring’.

Estimates for the number of killed vary depending on the source, and the United Nations has stopped providing regular numbers due to lack of reliable information.

Instability surrounding Iran’s nuclear program

March 28, 2013

Iranian elections are scheduled to take place this spring, and elections inside Iran have the ability to trigger political instability and upheaval. These elections could change the political calculus and the national conversation around Iran’s nuclear issue. Possibly sensing this, Ayatollah Khomeini, the Iranian supreme leader, announced in a speech last week that he may be interested in reopening political channels with Israel and the United States to negotiate Iran’s nuclear program.

The upcoming Iranian elections (and any instability that results) could complicate the strategic political decision the Iranian regime makes whether to actually build a weapon.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said in their latest report that the Iranian effort to develop a capacity to produce nuclear weapons persists. The enrichment process continues in an effort to reach bomb grade levels at 20 percent, the number of centrifuges at the Fordow facility, which is the Iranian facility that intelligence agencies are worried about.

Last September Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu gave a speech at the United Nations where he held up an image of a cartoon time bomb and said that Israel could no longer tolerate Iran’s uranium enrichment after this summer, because that would be the time when Iran would reach a point of no return. Mr. Netanyahu warned that Israel would have to forcefully intercede before this happens. Israel sees a strike on Iran as a war of necessity, because Israel believes a nuclear Iran is a threat to its security.

Consequently, Iran is facing both national elections and an Israeli deadline for war.

Were Israel to bomb Iran, there is the very real possibility that it might set off a regional war. I say this because both Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian territories would come to Iran’s defense.

The Lebanese Hezbollah has operated as an instrument for the radicalized Shi’ite community. Iran is seen as the de facto leader of the alliance between Shi’ite Muslim states, because the biggest effect the Iranian Revolution of 1979 had on the Middle East was to encourage the most uncompromising elements within the Shi’ite community to fight a regional counteroffensive against what was then a Sunni status quo.

Syria has long been an important mechanism for arming pro-Palestinian militant groups to fight Israel inside Gaza. With the civil war in Syria refusing to abate, Hamas currently lacks the ability to re-arm itself like it once did in the past; therefore, Hamas now depends more heavily on Iranian power.

Furthermore, the United States is in the process of drawing down its troops in Afghanistan. The Iranians will do everything possible to turn up the heat on American forces in Afghanistan if Israel attacks Iran.

Iranian supplies to the Taliban and to other groups within Afghanistan cannot be trivialized. Insurgents have long moved freely across the border Iran shares with Afghanistan, and Iran has been a safe haven for members of the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and others hiding from Western intelligence.

Sunni governments in the Middle East are also afraid of Iran acquiring a nuclear weapon. The Shi’ite faith has always appealed to the poor and oppressed waiting for salvation. Iran’s propaganda promotes an “Islam of the people,” and incites the poor to rise up against the impiety of Sunni-lead governments. An empowered and emboldened Iran would complicate the fragility of the region.

The Middle East has been dominated by Sunni power centered in Saudi Arabia since the creation of the Islamic conference in 1969. However, Iran has considered itself the true standard-bearer of Islam since its revolution, despite its Shi’ite minority status. Iran considers the Saudis to be “usurpers who sold oil to the West in exchange for military protection–a retrograde, conservative monarchy with a facade of ostentatious piety” (Kepel 2000).

Shi’ites currently make up about 15% of the Muslim population worldwide. The Shi’a were an early Islamic political faction (Party of Ali) that supported the power of Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the fourth caliph (ruler) of the Muslim community. Ali was murdered in 661CE, and his chief rival, Muawiya, became the new caliph. It was Ali’s death that led to the great schism between Sunni and Shi’ite.

Back to Iran, the south eastern region of country is volatile due to narcotics trafficking. The area is known as a gateway for smuggling drugs from Afghanistan and Pakistan into Western Europe. Therefore, elements of the Taliban and al-Qaeda have connections with Sunni insurgents working there.

Jundullah (Army of God) is a Sunni resistance group openly opposed to the Shi’a led government of Iran. Jundullah first made a name for itself in 2003, and it is believed that Jundullah was founded by a Taliban leader out of Pakistan named Nek Mohammed Wazir. Jundullah has a sectarian/ethnic agenda: the group wishes to free the millions of Sunni Balochs which it alleges are being suppressed by Tehran.

The Taliban and al-Qaeda’s regional influence has spread, and Jundullah has used suicide bombers, a hallmark of the al-Qaeda playbook, in it’s attacks against Iran. This indicates that Jundullah militants are likely receiving training from al-Qaeda (possibly within Pakistan’s borders), and one can only speculate how al-Qaeda would seek to take advantage of Iran turning into a war zone.

We’ve already seen al-Qaeda fighters pouring into Syria from Iraq to promote a jihadist vision that is fanatically anti-Shi’a. Al-Qaeda’s main grievance with the Syrian regime is that it is run by Alawites, people who belong to a branch of Shi’a Islam. Syria’s population is over 70% Sunni, yet the country is run by minority Shi’ites who make up only around 12% of the population. Al-Qaeda wants to change that, and it would love nothing better than to also install a Sunni government inside Iran.

As I said in my previous post, much of the Middle East remains politically unstable, because most modern Muslim states are only several decades old and were carved out by now-departed European powers. Cobbled-together states (a Sunni ruler over a majority Shi’a population or vice versa) highlight the artificiality and fragility of the Middle East and Muslim politics.

Iran is populated primarily by Shi’ites, and it remains a security (mukhabarat) state whose rulers focus on retaining their power and privilege by focusing on military and security forces at the cost of societal modernization. Islamic revivalism has stunted Iran’s march toward “Western” modernization, and is a prime example of what I was speaking of in my previous post when I said “a trend toward Westernization in Muslim societies has created a growing social split.”

Iran’s official language of Persian (Farsi) helps to keep Iran culturally isolated from much of the Middle East where Arabic is the dominant language. While Persian and Arabic share an alphabet, they are completely different languages with completely different pronunciations. This causes difficulties with Iran sharing in cultural products such as news, entertainment, and religious services with the majority of the Middle Eastern region. This fact is especially important to remember when we consider Iran’s communications (or lack thereof) with other countries in the Middle East. A lack of clear communication could complicate and escalate any conflict brewing in the region.

Iran, under the shah, wanted 22 nuclear reactors for energy, and at the time the United States supported this position. Iran only ever built one, but it has plans, it says, for others, but it’s taken a very long time to get to the point where it can build them. The question is, is Iran’s current regime also moving toward a weapon. Iran is supposed to declare everything that it’s doing on the nuclear front with the IAEA, but it has not cooperated with the international community in terms of giving it access to its scientists or in providing information on what it has been doing. Iran has blocked the IAEA at every turn, and it is currently in violation of the international agreements it has signed.